[ad_1]

As one will get older, reminiscences of previous occasions and outdated associates are likely to fade, however in addition they change into extra essential as milestones alongside (to resort to cliché) life’s busy freeway. A listing of my modest artwork assortment not too long ago introduced this house to me, because it prompted recollections of my early days in Burma (as Myanmar was then recognized).

I used to be posted to the Australian embassy in Rangoon (now Yangon) as Third Secretary in January 1974. I lived in Burma (as Myanmar was then recognized) for 2 and a half years, leaving in August 1976. I didn’t absolutely respect it on the time, however I used to be there throughout a interval of appreciable motion within the native artwork scene, which I first stumbled throughout accidentally, however later got here to embrace.

The principle purpose for my growing curiosity on this topic was my friendship with Solar Myint and his two sisters, Tin Tin Sann and Khin Myint Myint. All three had been very gifted artists, who collectively had a significant and lasting impression on the native artwork scene. I additionally turned good associates with one other famous Burmese artist (and creator), Ma Thanegi.

Not lengthy after my arrival in Rangoon, I used to be invited to dinner by the diplomat I used to be on account of change. He needed to present me a possibility to examine the bungalow on Monkey Level Highway (now Thanhlyet Quickly Highway) the place I used to be to dwell throughout my posting. It had initially been constructed for the supervisor of the oxygen fuel manufacturing facility close by, and consisted of two bedrooms and a kitchen/laundry surrounding a big open plan residing/eating room.

This design was nicely suited to the tropical local weather and to the life-style anticipated of a nationwide consultant. Nonetheless, the massive open space, characterised by excessive ceilings, broad archways and white partitions, appeared to me reasonably stark and empty. After I remarked on this reality, my host defined that he had coated the partitions with work by native artists, however they’d already been packed away in preparation for his return to Australia.

It was then that I made a decision to seek for appropriate artworks of my very own to embellish the home, enliven the environment of the principle residing areas and supply me with some unique souvenirs of my first abroad posting.

“Sub Aqua” by Khin Myint Myint (provided by creator)

My reminiscences of these days should not as clear as they as soon as had been, however I can vividly recall my first encounter with the Burmese artwork world.

Earlier than I started work within the embassy full-time, I used to be given six weeks to check the Burmese language, with an area tutor. For this era, I stayed within the then 73 year-old Strand Resort, which was located simply throughout Seikkantha Road from the embassy, within the coronary heart of the capital. To assist get my bearings in a brand new place, and develop an ear for the unfamiliar sounds and tones of Burmese, I used to take lengthy walks across the metropolis.

It was not lengthy earlier than I got here throughout the Lokanat Artwork Gallery, across the block from the Strand Resort, at 58-62 Pansodan Road. The gallery had been established in 1971, in an outdated Italianate constructing inbuilt 1906 by Thomas Swales and Isaac Sofaer. Initially often known as Sofaer’s Constructing, it was a prestigious business tackle throughout the British colonial interval, with the Financial institution of Burma and Reuters Information Company amongst its tenants.[1]

The gallery was based by a former army officer and creator, Dhammika U Ba Than, and an legal professional, U Ye Htoon. They invited 20 main members of Burma’s artwork world to change into founding members of a cooperative enterprise. Their purpose was to offer a venue for exhibitions and to assist up to date artists make a residing from their work, one thing that had confirmed tough since Common Ne Win seized energy in a army coup in 1962.

Associated

Picture-making as necessity in Preventing Concern II

A latest exhibition showcased Myanmar artists’ responses to the coup and resistance to it.

The image of the gallery was Lawkanat, or Lokanatha, believed to be the Burmanised type of the Buddhist bodhisattva, Avalokiteshvara. He represented peace and prosperity and was recognisable by his distinctive headdress. The gallery’s signage and publicity materials depicted the determine in each conventional and stylised kinds. Consistent with this theme, the motto of the gallery was “Fact, Magnificence, Love”.

The Lokanat quickly established itself as an essential venue for show-casing and promoting trendy Burmese artwork.

In early 1974, the doorway to the gallery was simply missed. It was poorly sign-posted at road stage and the doorway to the constructing was crowded with road stalls promoting betel nut, slaked lime and different condiments. Additionally, the exhibition area was on the primary ground, hidden away up a flight of dim and dusty stairs. I bear in mind pondering on the time that the outdated picket banister was unsafe and couldn’t be relied upon.

To my shock, nevertheless, this reasonably off-putting entryway led to 2 very massive, ethereal rooms, with flooring coated in enticing vintage tiles. The partitions had been white-washed and hung with vibrant oil work, water colors and framed sketches. They had been by a combination of established artists like U Hla Shein, who painted in conventional Western types, and new and rising artists experimenting with extra trendy methods.

Most work on show within the Lokanat had been portraits, or landscapes. They coated the standard topics of pagodas, Buddhist monks, paddy fields and bullock carts. These had been the timeless, if reasonably clichéd, themes that had attracted British painters and artwork lovers from the earliest colonial days, when civil servants, troopers and vacationers developed a style for creative works depicting the native surroundings and conventional Burmese life.

Portray of a Burmese lady by Gerald Festus Kelly

Certainly, by the hands of painters like Gerald Festus Kelly, Robert Talbot Kelly and Frederick Goodall, work of Burmese individuals and scenes turned enormously in style in Britain, the US and elsewhere.[2] Along with photographers like Felice Beato, Philip Klier and others, they helped set up Burma’s fame as a land of golden pagodas and delightful girls. These romantic photographs are nonetheless being peddled by journey brokers.[3]

“On the Highway to Mandalay” by Frederick Goodall

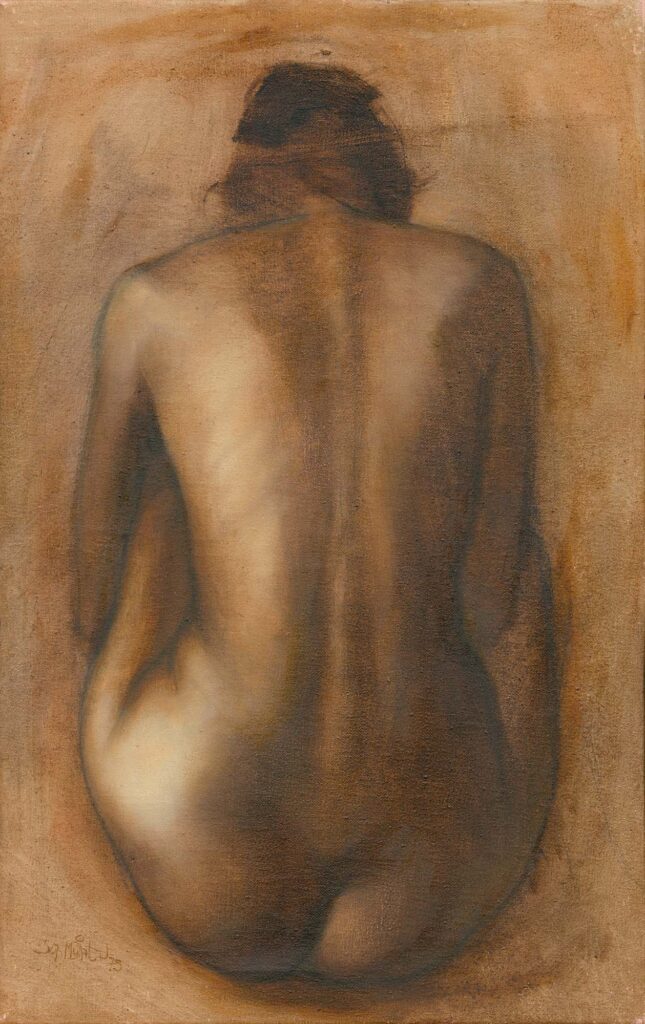

The Lokanat, nevertheless, additionally exhibited different works, by artists with an unique strategy to types and supplies. One work in my assortment by Khin Myint Myint, for instance, employed gold leaf to focus on features of the figures within the portray. I even have a few nudes by Solar Myint, in his trademark sepia and sienna colourings. The latter had been bought privately, nevertheless, as censorship of native artworks was then a significant problem.

A portray by Solar Myint (provided by creator)

I can’t bear in mind the names of all of the artists represented within the Lokanat and the few different galleries working round that point, however a quantity stand out in my reminiscence—primarily as a result of I later bought work by them. Along with works by Solar Myint, Tin Tin Sann, Khin Myint Myint and Ma Thanegi, I acquired oil and acrylic work and water colors by the likes of Paw Oo Thet, Win Pe, Tin Win and Sai Kyaw Htin.

Some native artists had obtained disciplined, formal coaching in Burma, whereas others had been largely unbiased and self-taught.

Round this time, there have been numerous influential artwork lecturers, like U Lun Gywe, who mentored the younger Solar Myint. A couple of had been overseas, for one purpose or one other, and will draw inspiration from museums and galleries visited throughout their travels. Most, nevertheless, relied on conventional types and the realist custom left behind by the British. Others, nevertheless, looked for examples of various genres in artwork books and magazines.[4]

The first marketplace for unique artwork works in Myanmar within the Seventies was resident foreigners. Nearly all had been members of the diplomatic neighborhood, then solely about 1,200 robust. They had been nicely paid and plenty of had been focused on buying mementos of a posting in an unique and comparatively distant a part of the world. Customer visas had been initially restricted to 24-hours, later prolonged to seven days, successfully ruling out gross sales to vacationers.

Earlier than my arrival in Burma in 1974, diplomats usually staged “free” artwork exhibitions of their embassies and houses. They had been a preferred type of leisure in a metropolis largely devoid of standard night time life. These non-public features gave native artists full rein to specific themselves, “free” from authorities restrictions. They had been additionally a welcome supply of earnings for the artists, as few work had been left unsold on the finish of such reveals.

These features, nevertheless, aroused the ire of the authorities, who resented the truth that the official censors had been being bypassed. Nor did they like members of the native inhabitants fraternising with outsiders, notably the officers of overseas nations, who had been all the time seen with suspicion. It was suspected, for instance, that some diplomats had been making an attempt to encourage freedom of expression, one thing anathema to the socialist regime.

After 1967, free reveals on non-public premises required a authorities allow, a measure which successfully killed them off.[5] Nonetheless, this improvement inspired native artists and galleries to organise their very own exhibitions. Over the following decade there have been about three dozen main exhibitions, involving some thirty or so artists.

“Meditation 2” by Khin Myint Myint (provided by creator)

Public exhibitions, nevertheless, had been topic to heavy-handed censorship. As much as a dozen officers from the federal government’s Censorship Board and different businesses may flip as much as study the work collected for a present, and interrogate particular person artists about their work.[6] For sure, these officers had been chosen for his or her dedication to the army regime, reasonably than for any information of, and even curiosity in, visible artwork.

Any works that had been deemed crucial of Ne Win’s socialist authorities or the armed forces, irrespective of how remotely, had been deemed unacceptable and banned from show. If Burma’s conservative cultural norms had been believed violated, for instance by the depiction of nudes, they too had been banned. Experimental artwork was additionally seen as implicitly crucial of previous methods of life, and thus a problem to the regime’s isolationist insurance policies.

After the introduction of a brand new structure in 1974, and the switch of energy from Ne Win’s Revolutionary Council to a supposedly elected civilian authorities underneath the Burma Socialist Programme Occasion, the extent of artwork censorship in Burma appeared to extend. Even the usage of sure colors was thought-about subversive. Work deemed offensive had been stamped “not allowed to indicate” on the back and front. Some works had been confiscated and infrequently the artist was even detained.

As Melissa Carlson has written, “within the authorities’s quest to say its authority, the censorship of exhibitions quickly resulted in a state-sanctioned genus of art work that drew on idyllic but conservative portrayals of Burma”. [7] Some more moderen observers have admired the perceived emphasis on Burma’s “pastoral, Buddhist-resplendent glory”.[8] Nonetheless, within the Seventies this development truly mirrored a state-sanctioned template that “stripped canvasses of any actual or imagined socio-political commentary”.[9]

One other issue confronted by native artists round that point was the scarcity of supplies. Regardless of strict financial laws limiting overseas imports, it was typically attainable to purchase paints and canvases from authorities shops. Nonetheless, they had been all the time in brief provide. Many artists relied on the generosity of overseas associates who had been in a position to herald paints and canvasses from overseas, often by visiting artwork suppliers in Bangkok.

Portray by Tin Tin Sann (provided by creator)

Regardless of all these issues, nevertheless, the artists of the Lokanat Gallery and different retailers, just like the Peacock Gallery, continued to work, demonstrating not solely their abilities for illustration and interpretation, but additionally innovation.[10] More and more, Burmese artists experimented with completely different types, together with cubism and summary artwork. The native artwork scene, whereas small and remoted from many exterior influences, was a surprisingly vibrant one.

Throughout the Seventies, Solar Myint performed a big position in all these developments. In 1971, he turned a founding member of the Lokanat Artwork Gallery. By the point I arrived in Burma three years later, he was already well-established within the native artwork world, and contributed many unique works to the sphere. Between 1968 and 1977 he participated in a minimum of eight main exhibitions and contributed to numerous reveals in non-public properties.[11]

Alongside together with his sisters Tin Tin Sann and Khin Myint Myint, Solar Myint was additionally a member of the influential Modernist Motion, which was energetic in Yangon and Mandalay between the late Nineteen Sixties and late Seventies.

Solar Myint has been described as a member of the realist faculty, however I bear in mind him experimenting with different approaches, prompted partly by illustrations he noticed in a historical past e book about Western portray. Even his traditional works contained hints of different types. He was additionally ready to push the boundaries of official censorship. His nudes, for instance, had been eagerly wanted by members of the diplomatic neighborhood. They had been often painted on canvas set on board, in atmospheric sepia colourings.

One in every of his work stands out in my thoughts as a great instance of Solar Myint’s strategy to artwork on the time. It was titled “The Pilgrims” and depicted a horse-drawn cart, beneath a steep escarpment on which there have been a number of golden and white pagodas [see image above the title of this article]. The scene was finely drawn, with an exquisite use of color, however what I preferred most about it was the artistic use of clean area, nearly like a standard Chinese language ink portray. This gave the work an exquisite ethereal, other-worldly really feel.

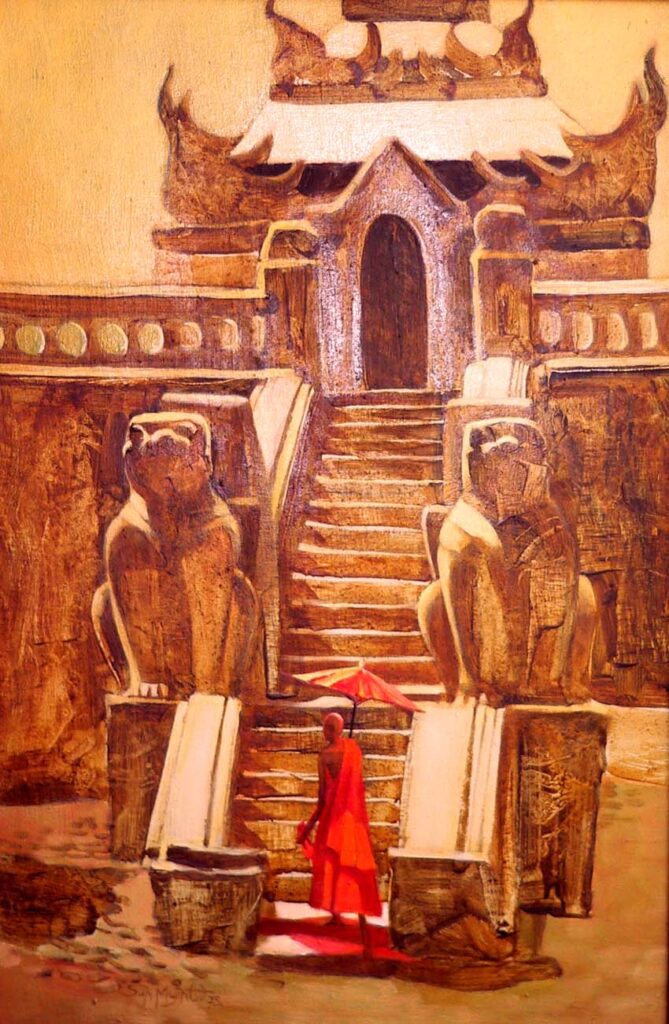

One other acquisition of mine was an oil portray [see below] of a Buddhist monk on the steps of the Pitakat-Taik, within the historic capital of Pagan (now Bagan). It stands other than different work on this style by Solar Myint’s distinctive use of a yellow/brown/crimson palette, with colors starting from cadmium yellow to burnt sienna. Additionally, the sides of the constructing and the standing determine are softened, and the variations between gentle and shadow are emphasised, to present a distinctly impressionistic really feel to this timeless scene.

A portray by Solar Myint (provided by creator)

Tin Tin San’s work coated a spread of genres, however my eye was caught by one particularly. It was an impressionistic oil portray of boats on Pazundaung Creek, close to my house on Monkey Level Highway. Like her different work with a maritime flavour, it’s a vibrant and evocative work, relying closely on gentle sienna and different wealthy earth colors to seize the photographs of small boats moored by a jetty, with gentle shimmering on the water.

A portray by Tin Tin Sann (provided by creator)

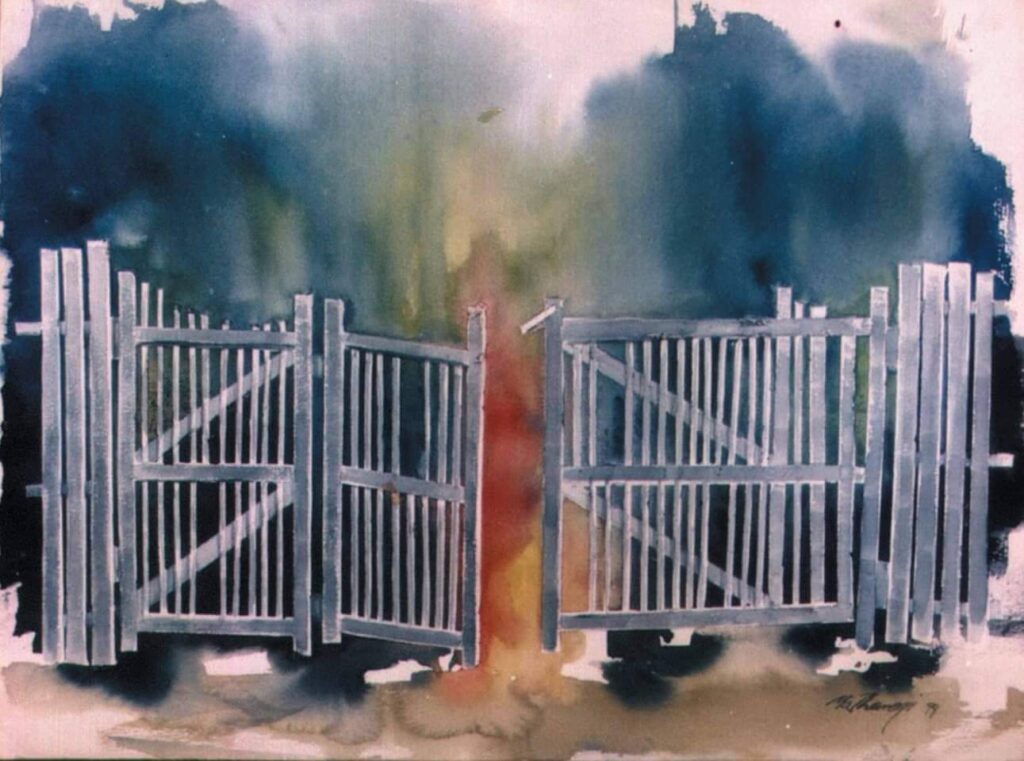

Ma Thanegi too had a effective eye for type and line, and will paint extremely correct and life like nonetheless life and panorama work, and portraits, in each oils and water colors. Nonetheless, like her buddy Khin Myint Myint, she too experimented with different artwork kinds, together with the usage of completely different mediums. I nonetheless have a big framed batik of a bilu (Burmese ogre) she made throughout one among her forays into the craft world.

Portray by Ma Thanegi (provided by creator)

Portray by Ma Thanegi (provided by creator)

Portray by Ma Thanegi (provided by creator)

Today, I don’t have the wall area in my modest suburban home to hold all my Burmese work. Some works have been returned to their creators and some have been given away as presents. Nonetheless, these work that stay are potent reminders of these far-off days after I was a neophyte diplomat progressively attending to know an unique, if tragically misgoverned, land by the medium of its artists and visible artwork.[12]

References

To return to your house within the textual content, click on the footnote quantity

[1] Affiliation of Myanmar Architects, 30 Heritage Buildings of Yangon: Contained in the Metropolis that Captured Time (Chicago: Serindia Publications, 2012), pp.81-5.

[2] Greater than 50,000 prints of Gerald Kelly’s portraits of Burmese “princess” Sao Ohn Nyunt have been bought. They’re nonetheless accessible in the present day. See Christian Gilberti, “An Irish Painter in Burma: Sir Gerald Kelly”, Myanmore, 4 March 2020, at https://www.myanmore.com/2020/03/an-irish-painter-in-burma-sir-gerald-kelly/

[3] Andrew Selth, Making Myanmar: Colonial Burma and Fashionable Western Tradition (revised model), Analysis Paper (Brisbane: Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith College, 2020).

[4] For instance, one monochrome portray by Paw Oo Thet, of a feminine Burmese dancer, was reportedly impressed by “The Peacock Skirt”, a print by the 19th century British illustrator Aubrey Beardsley.

[5] Andrew Raynard, Burmese Portray: A Linear and Lateral Historical past (Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2009), p.216.

[6] The Censorship Board was overseen by the Press Scrutiny and Registration Division of the Ministry of Data. It was staffed on a rotating foundation by appointees from a spread of presidency departments and safety businesses. See Ian Holliday and Aung Kaung Myat (eds), Portray Myanmar’s Transition (Hong Kong: Hong Kong College Press, 2021), p.6.

[7] Melissa Carlson, “Portray as Cipher: Censorship of the Visible Arts in Put up-1988 Myanmar”, Sojourn: Journal of Social Points in Southeast Asia, Vol.31, No.1, March 2016, pp.116-72.

[8] Peter Janssen, “Golden Land Unveiled”, Asian Enterprise, April 1995, p.63.

[9] Carlson, “Portray as Cipher”, p.121.

[10] The Peacock Gallery opened in 1975 and closed in 1986. Whereas small, with solely 9 members, it had a significant impression, partly by exhibitions of works utilizing such various mediums as batik, papier decoupages and collage. See Ma Thanegi (ed), Myanmar Portray: From Worship to Self-Imaging (Ho Chi Minh Metropolis: Training Publishing Home, 2006), p.76.

[11] Raynard, Burmese Portray, p.217.

[12] Andrew Selth, “Burma After Forty Years – Nonetheless Not like Any Land You Know”, Griffith Overview, 26 April 2016, at https://www.griffithreview.com/wp-content/uploads/Selth.Burma_.Essay_.Final_.set_.pdf

[ad_2]

Source link