[ad_1]

Ask the common Indonesian voter what they imagine it takes to be a profitable legislative candidate and also you’re probably get the response: “harus punya duit”—“[they] will need to have cash.”

These voters’ intuitions are backed up by loads of analysis exhibiting that political campaigns in Indonesia are costly—and that prices are on the rise. To face an opportunity in any legislative election, would-be politicians should pay the salaries of sprawling marketing campaign groups, buy mountains of marketing campaign paraphernalia, and hand out envelopes of money to voters on election day. These prices can come to over US$50,000 for a candidate on the district or metropolis degree; for nationwide parliament, political aspirants can spend upwards of US$2 million. Particular person candidates, reasonably than their get together, foot the invoice, and failure to win workplace can result in monetary break. Given the plain benefits that non-public wealth affords a candidate in such a system, it’s little shock that businesspeople and oligarchs are getting into politics in rising numbers.

All of those realities had been on show in February 2024, when Indonesia held elections for metropolis, district, province and nationwide legislatures alongside its presidential poll. Legislative candidates we’ve spoken to described the marketing campaign as financially “brutal”, with the massive sums of cash spent by tens of hundreds of candidates prompting some to conclude that this yr’s elections had been the costliest in Indonesia’s democratic historical past.

Given the spiralling prices of campaigning, it’s unsurprising that voters imagine solely the rich can run for workplace. However simply how rich does one have to be to win a seat in parliament in Indonesia? And do some candidates want more cash than others? Up to now, researchers haven’t had the sort of knowledge that may systematically examine the impact of legislative candidates’ private wealth and marketing campaign spending on their possibilities of electoral success. To fill this hole, we used the 2024 elections to conduct a novel survey of candidates that for the primary time permits us to check the extent to which wealth begets illustration in Indonesia’s native legislatures. We additionally discover the extent to which cash offsets countervailing elements thought to harm candidates’ possibilities of success. Do candidates who face “demographic headwinds”—for instance, girls—want more cash to offset their electoral drawback? On the flip facet, do some candidates want much less cash, like these with dynastic connections, who can use their title and networks for electoral achieve?

The information

To discover these questions, we use the primary panel survey of legislative candidates ever performed in Indonesia. Beginning in November 2023 we labored with Saiful Mujani Analysis and Consulting to survey a random pattern of candidates working for seats in metropolis (kota) and district (kabupaten) degree legislatures (DPRD Tingkat II). Out of feasibility considerations, we imposed a number of restrictions on the pool of candidates, proscribing our pattern to candidates within the first three positions on their get together lists, and who had been working with events that had been polling above 1% as of 1 October 2023. We additionally excluded candidates working in Papua and Maluku over considerations concerning the prices related to surveying respondents in hard-to-reach areas.

Our survey was a panel, that means we tried to survey the identical 800 candidates thrice: twice earlier than the election, in November 2023 and January 2024, in addition to as soon as after the election, in April 2024. Ultimately, we obtained an 81% recontact charge, that means roughly 650 candidates had been surveyed in all three waves. We imagine these knowledge thus supply a uniquely fine-grained portrait of the evolving attitudes and behaviours of legislative candidates over the course of their campaigns.

The findings

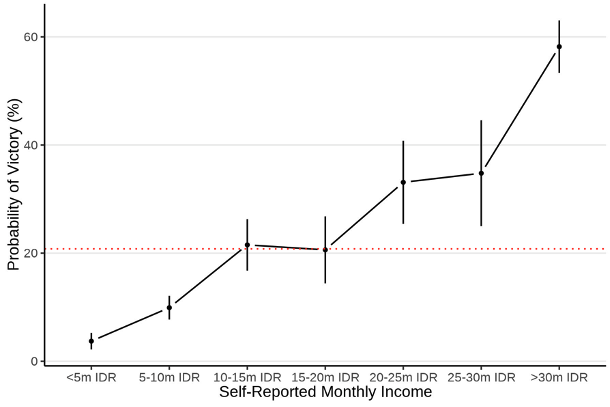

We set up a number of stylised info concerning the relationship between wealth and illustration in Indonesia, which characterise a bigger phenomenon we intend to discover in a collection of associated articles utilizing this new dataset. First, in Determine 1, we discover a putting linear relationship between wealth and electoral success (the dotted crimson line represents the general probability of victory, i.e., ~20%). The richer the candidate, the extra probably they’re to win a legislative seat. To place this discovering in concrete phrases: in comparison with the poorest candidates (those that earn lower than Rp5 million per thirty days), the richest candidates (those that earn greater than Rp30 million per thirty days) are greater than fifteen instances as more likely to win their race.

Determine 1: relationship b/w candidate revenue and chance of victory

As a result of campaigns are mainly self-funded on the native degree in Indonesia, rich candidates spend greater than their poorer friends. However what do rich candidates spend their cash on to safe larger possibilities of victory?

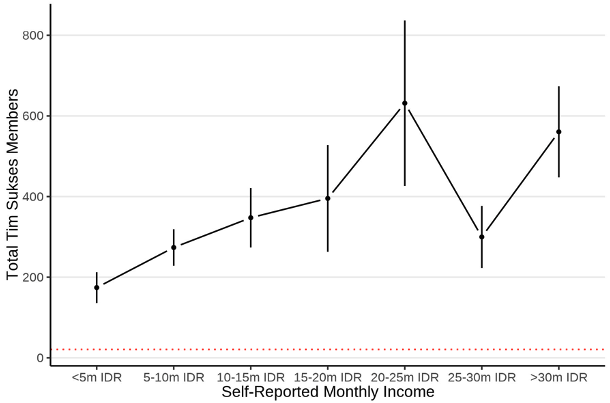

Our survey reveals no adjustments within the composition of their spending: wealthier native candidates proceed to spend appreciable sums of cash on baliho (banners) and the acquisition of votes. In different phrases, richer candidates should not extra more likely to undertake completely different and extra refined marketing campaign methods. As an alternative, what we unearth is proof that richer candidates are merely capable of construct bigger marketing campaign groups (tim sukses). Determine 2 reveals the scale of candidates’ marketing campaign groups in line with their month-to-month revenue, exhibiting that richer candidates are capable of spawn patronage networks which can be thrice as giant as their poorer challengers.

Determine 2: relationship b/w candidate revenue and marketing campaign crew measurement

These findings won’t come as a shock to observers of Indonesian politics. Our principal curiosity on this venture, nonetheless, is in understanding the extent to which cash issues in Indonesian elections. On this depend, the magnitude of our discovering deserves a re-evaluation. Cash merely dwarfs different standard predictors of success: compared, take into account that males are solely two and a half instances extra more likely to win than girls; these with tertiary levels are thrice as more likely to win in comparison with these with solely a highschool diploma; and, the oldest candidates are solely twice as more likely to win because the youngest.

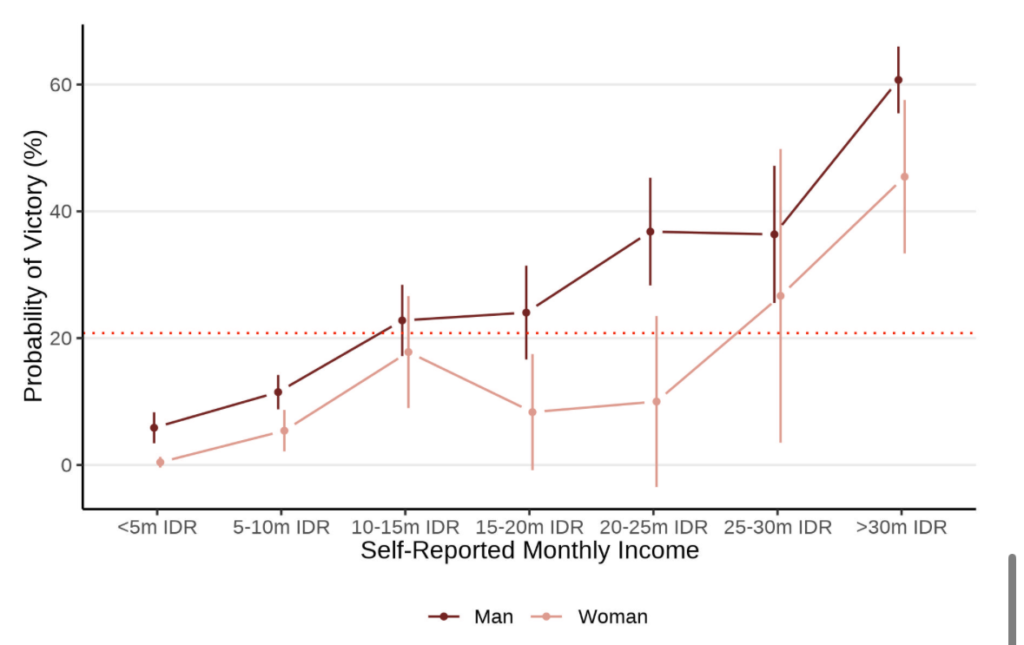

Briefly, the benefit loved by rich candidates outstrips just about each different characteristic considered predictive of electoral success. We discover these ends in larger depth in Figures 3 and 4. Take gender, in Determine 3, for instance. Wealthy males typically carry out higher than wealthy girls. And males are usually richer than girls. However, wealthy girls carry out significantly higher than poorer males. As an example, a girl who stories incomes greater than Rp30 million per thirty days has a 42% probability of success, which is roughly eight instances bigger than the 5% probability of success reported by a person who earns lower than Rp5 million per thirty days.

Determine 3: relationship b/w candidate revenue and chance of victory, by gender

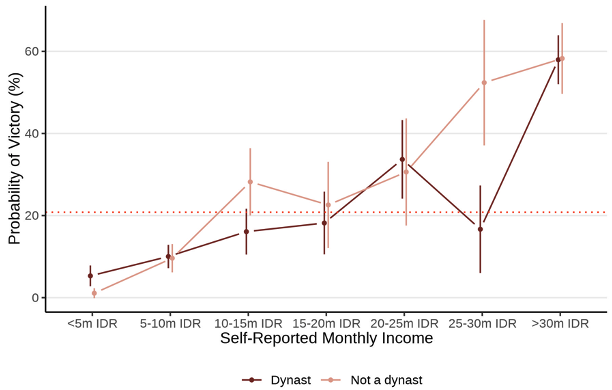

In Determine 4, we conduct a similar evaluation a candidate’s standing as a member of a political dynasty (or not). With Gibran Rakabuming Raka’s current election as vp on Prabowo Subianto’s ticket, analysts of Indonesian politics are rightly attuned to the affect of nepotism in structuring electoral politics. However Determine 4 reveals that one’s standing as a dynast is in reality inconsequential when considered in gentle of the electoral benefit of wealth. Certainly, it could be the case that dynasts and incumbents carry out higher just because they’re wealthier than their rivals—not due to any inherent benefit conferred by the political networks coming with these positions. Determine 5 reveals, in keeping with this, that rich dynasts have equal electoral prospects to rich non-dynasts—and that this relationship holds throughout the revenue distribution.

Determine 4–Relationship b/w Candidate Earnings and Chance of Victory, by Dynasty

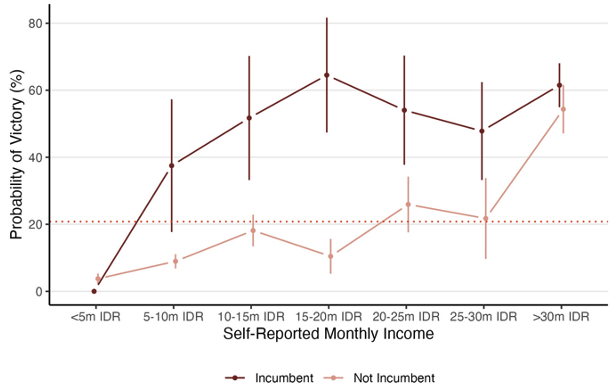

One exception to our findings considerations the function of incumbency. Determine 5 reveals that, as soon as in workplace, poorer candidates do roughly in addition to their richer friends—though a slight electoral drawback continues to exist. To quote concrete numbers, 40% of incumbents who earn Rp10 million a month received their contests, in comparison with 60% of incumbents who earn greater than Rp30 million a month.

The attenuated relationship between wealth and victory amongst incumbents probably derives from their potential to deploy state sources to their electoral benefit, wealthy or poor, as soon as in workplace. In step with this interpretation, non-incumbents exhibit the identical constructive relationship between revenue and chance of victory. Although, as soon as a non-incumbent candidate earns greater than 30 million per thirty days, their chance of profitable the election is statistically indistinguishable from an incumbent’s.

Determine 5: relationship b/w candidate revenue and chance of victory, by incumbent standing

Conclusion

The survey knowledge paint a remarkably clear image of the function that wealth performs in Indonesia’s legislative elections. We’ve recognized for a while that “cash issues”. However the relationship we uncover right here between revenue, spending, and electoral success is arguably extra dramatic than present research have advised. Of specific significance is how these knowledge illustrate the benefit that wealth affords political candidates over and above different traits typically assumed to play a figuring out function in electoral victory, akin to dynastic connections. There’s little doubt that entrenched patterns of clientelism and under-financed political events have, during the last twenty years, pushed up the price of politics and created obstacles to entry for much less rich candidates.

Analysts have a much less agency grasp on exactly what it means for the standard of Indonesia’s democracy if the nation’s consultant establishments change into accessible solely to the very wealthy. On the one hand, among the basic work on politicians’ backgrounds suggests class has little affect on the sorts of issues they do in workplace—primarily in contexts the place there’s a sturdy programmatic get together system such that politicians’ actions are constrained and formed by get together ideology and platform.

Alternatively, in a political system like Indonesia’s, the place programmatic politics are weak, class backgrounds probably matter extra for the way politicians behave in workplace, what they prioritise, and what sort of insurance policies they pursue. The information we current right here counsel this is a crucial line of enquiry for future analysis, given there’s little to point that rising political prices will reverse any time quickly.

[ad_2]

Source link