[ad_1]

Electrical bikes are a viable various to vehicles in city areas, however how efficient they’re at decreasing carbon emissions is unclear. This column finds {that a} 2018 Swedish e-bike subsidy programme was profitable in persuading individuals to purchase an e-bike, and there was appreciable substitution of biking for driving. Nevertheless, for the programme to be cost-effective, the social value of carbon a lot increased than the $50 to $100 estimates steadily mentioned. Different social advantages, resembling stimulating adoption, selling well being or decreasing congestion, are wanted to encourage these interventions.

Emissions from transportation account for about 29% of whole US greenhouse gasoline (GHG) emissions, making it the biggest contributor by sector to international warming.

Throughout the transportation sector, vehicles alone are chargeable for 58% of all transportation emissions, in line with the US Environmental Safety Company. Together with electrical vehicles, electrical bikes or pedelecs (e-bikes) are a doubtlessly essential software to deal with international warming (Holland et al. 2015). With rechargeable batteries that make them able to lengthy distances, they will change automobile journeys for work in dense and rising city areas world wide.

Since e-bikes are comparatively costly, policymakers have launched subsidies to stimulate and velocity up adoption. Nevertheless, welfare evaluation of those e-bike subsidy programmes is difficult for a number of causes:

- Incidence: A welfare evaluation requires measures of how the subsidy is allotted between customers and producers. If provide is comparatively inelastic, producers compensate themselves for increased demanded portions.

- Additionality: Past sharing the excess, policymakers are involved that programmes entice extra customers and never profit solely those that would have transformed even absent any subsidy (Joskow and Marron 1992, Boomhower and Davis 2014).

- Substitution from driving: The second level additionally raises the difficulty of whether or not a household that buys an e-bike will essentially reduce down their driving or if the bike will substitute for different technique of transportation as an alternative.

Sweden’s e-bike subsidy

To handle these points, in Anderson and Hong (2022) we mix administrative, insurance coverage, and survey knowledge from a large-scale Swedish e-bike subsidy programme from 2018. The programme, which gave a 25% low cost on buy worth, is comparable in construction to programmes run and proposed in different nations. It was highly regarded. The one billion krona ($115 million) programme was supposed to final for 3 years, however exceeded its per-year spending restrict throughout its first 12 months, with nearly 100,000 e-bikes bought. The subsidy was for 25% of the retail worth, with a restrict of 10,000 kronas (or round $1,100).

Incidence

With a purpose to assess the impact of the subsidy on costs, we merge the subsidy knowledge with gross sales knowledge from a number one insurance coverage supplier for bicycles in Sweden, acquiring gross sales knowledge each inside and out of doors of the subsidy interval.

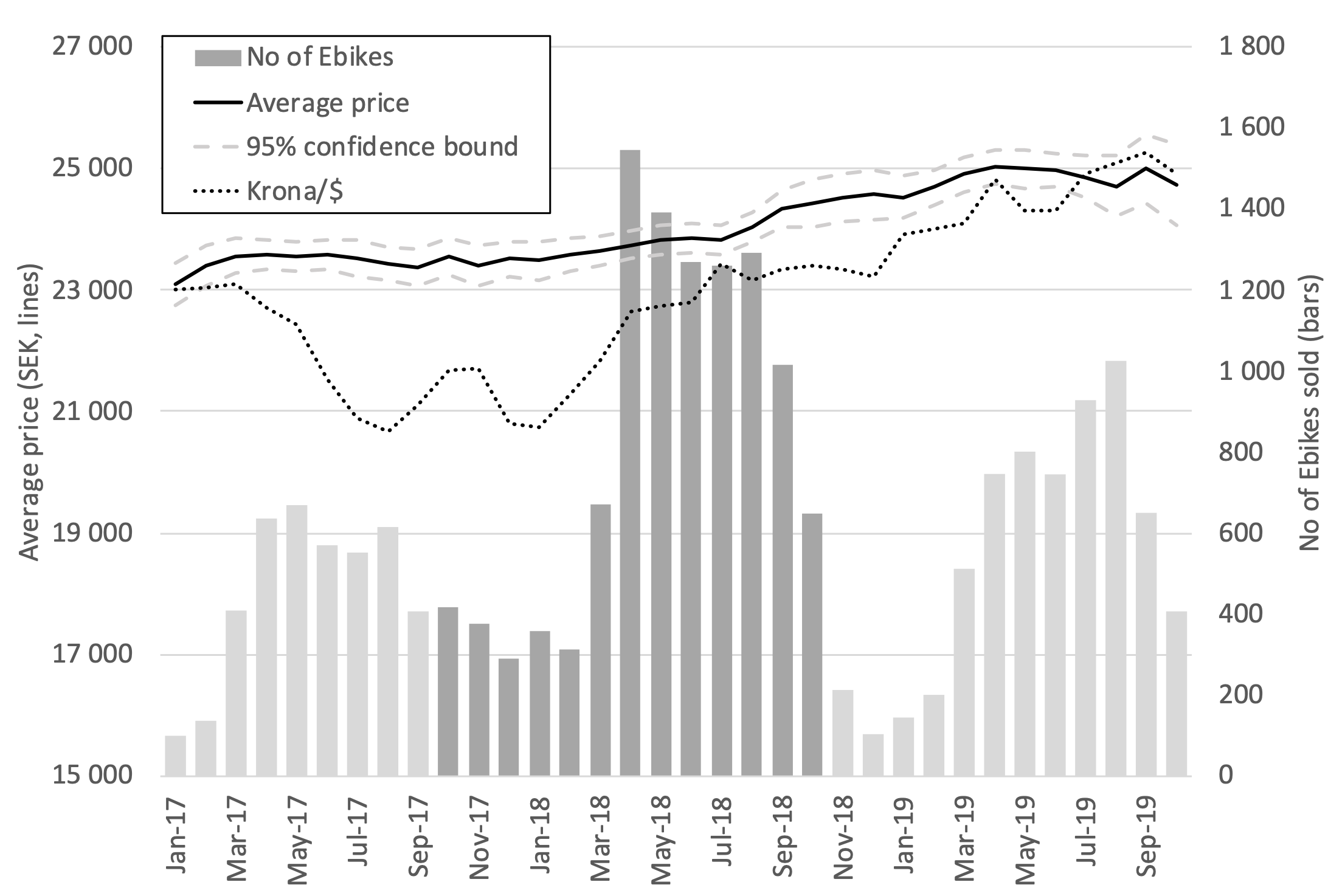

Determine 1 plots costs and volumes of the 38 high promoting e-bike fashions bought all through the interval throughout the nation’s 49 largest retailers, obtained by matching the 2 knowledge units. The daring line exhibits the common worth, which scarcely modified earlier than and after the introduction of the subsidy. The common worth is pushed by a depreciation of the foreign money (and a number of different fastened results that we take into account). We discover that all the low cost given customers by means of the subsidy landed within the arms of the customers.

Determine 1 Common worth and portions for high promoting e-bike fashions across the 2018 subsidy

Additionality

The gray bars of Determine 1 present the impact on portions, the place the darker shades point out the subsidy interval. In line with the general reported quantity improve, we discover that round 70% extra e-bikes have been bought through the subsidy. We additionally use the SEPA survey, which requested individuals to evaluate the significance of the subsidy, and discover that about two-thirds of customers wouldn’t have purchased the e-bike with out the subsidy.

Substitution from driving

For the ultimate piece of study, we’d like knowledge on driving behaviour earlier than and after the acquisition of the e-bike. Knowledge on commuting behaviour is accessible on the SEPA survey. We discover significant adjustments in automobile driving behaviour. Nearly two-thirds of our pattern report utilizing a automobile to some extent for commuting earlier than shopping for an E-bike, and greater than half use it each day. After having purchased the e-bike, solely 4% stored utilizing the automobile every single day and 54% used the automobile much less steadily (of this latter group, 23% stopped utilizing the automobile for commuting altogether). The change in commuting behaviour by automobile is extra pronounced than by different technique of transportation, resembling common biking or public transport. Apparently, we discover that the subsidy pick-up was comparatively bigger in much less populated areas and never in huge cities.

Carbon discount

For the ultimate piece of the evaluation, we put our outcomes collectively. The common per unit value for the subsidy quantities to round $500, however provided that it’s paid additionally to non-additional customers, this rises to $766 per extra unit bought. The information on modified driving behaviour permits us to drag out the common discount in automobile use for extra customers. Multiplying by means of with the common life-span of an e-bike and likewise bearing in mind the carbon footprint of the E-bike itself, we discover the common whole internet carbon discount to be 1.3 tonnes per extra e-bike. To interrupt-even at $766, the social value of carbon must be within the vary of $600 per tonne, which is way away from the $50 to $100 estimates steadily mentioned amongst economists (Nordhaus 2017). The principle conclusion is that the e-bike subsidy can’t be justified on the idea of the social value of carbon alone.

Dialogue

Our estimates don’t embrace potential incidental results attributed from lowered site visitors congestion, driving security, improved well being results, or peer results and elevated charges of adoption. A disproportionate pick-up of subsidies in huge cities speaks towards the subsidy being an efficient software for decreasing congestion. Driving security and well being aren’t solely troublesome to measure, however can go each methods. Automobile drivers represent 42% of our pattern of extra customers. For them, driving security might be lowered, although their general well being is optimistic. There are indicators of accelerating charges of adoption. Though Determine 1 exhibits a slowdown of purchases instantly after the subsidy, gross sales picked up shortly within the following interval. The counterfactual is difficult to estimate, however an elevated conversion fee on account of the subsidy may very well be an essential motivation for the subsidy that didn’t enter our calculations.

We doc a comparatively giant hole in value and profit based mostly on carbon financial savings emissions and depart it to future analysis to include these different social advantages into the evaluation.

References

Anderson, A and H Hong (2022), “Welfare implications of electrical bike subsidies: Proof from Sweden”, NBER working paper w29913.

Boomhower, J and L W Davis (2014), “A reputable method for measuring inframarginal participation in vitality effectivity program”, Journal of Public Economics 113: 67–79.

Holland, S, E Mansur, N Muller and A Yates (2015), “Analysing environmental advantages from driving electrical automobiles”, VoxEU.org, 09 August.

Joskow, P L and D B Marron (1992), “What does a negawatt actually value? Proof from utility conservation program”, The Power Journal 13(4).

Nordhaus, W D (2017), “Revisiting the social value of carbon”, Proceedings of the Nationwide Academy of Sciences 114(7): 1518–1523.

[ad_2]

Source link